Marlies Stappers Impunity Watch: "Putting victims at the centre is crucial to improving human rights"

Marlies Stappers Executive Director at Impunity Watch

On the occasion of Human Rights Day, we spoke with Marlies Stappers, the Executive Director of Impunity Watch. This dedicated organization tirelessly works to combat impunity globally and promote justice. The interview sheds light on current challenges in the human rights domain, with a specific focus on Impunity Watch's involvement in Guatemala and Syria.

Marlies not only shares her personal experiences but also critically examines the evolution of human rights activism. The core of the conversation emphasizes the importance of listening to the voices of victims and striving for meaningful victim participation in shaping and implementing policies that better align with the actual priorities of victims and reforming the root causes of violence and impunity.

Interview by Loretta Monique

World Human Rights Day is observed every year on December 10th. How does Impunity Watch actively contribute to the global discourse on human rights, and are there any special initiatives or events planned to mark this occasion?

"It is crucial to take a moment each year to reflect on the meaning of human rights and emphasize its universal nature, especially as human rights face increasing pressures. We live in a changed world marked by heightened polarization with significant geopolitical implications. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is aptly named 'universal,' reminding us that human rights apply to everyone. In the current context, it is incredibly important to seize such a day to reflect on the significance of defending human rights. I want to emphasize that human rights are not limited to just one day; it is something to be lived, conveyed, and demonstrated every day at work, behind the computer, and in the field. That is how we, at Impunity Watch, want to experience this day."

I want to emphasize that human rights are not limited to just one day; it is something to be lived, conveyed, and demonstrated every day at work, behind the computer, and in the field.

In your role as the Executive Director, how do you see the significance of World Human Rights Day in raising awareness and mobilizing support for the issues Impunity Watch focuses on?

"In all the countries where we are currently active, there are serious human rights issues. Two examples are Guatemala and Syria.

In Guatemala, recent elections took place in a country recovering from a civil war where peace accords were signed in 1996. Since then, a peace process has been underway, achieving much, but the implementation of the peace accords is a daily struggle for human rights defenders, victims, indigenous communities, and independent justice operators. Against all expectations, a 'good,' non-corrupt candidate won the elections with plans to address the significant issues in the country. The corrupt political, economic, and military elites are afraid of losing their privileges and impunity. They are doing everything to overturn the results and prevent the newly elected candidate from taking office on January 14th next year. What stands out and should be central on a day like December 10th is the immense strength of the indigenous population, which, under very difficult conditions, has been raising its voice for months, making it clear that they do not accept the ongoing coup. Currently, the massive protests in Guatemala are all led by indigenous communities, historically facing institutionalized racism, exclusion, and oppression. Despite extreme poverty and marginalization, they have been camping in the capital for over two months, voicing their opposition to corruption, election theft, and advocating for democracy and peace. During the Guatemalan civil war (1960–1996), genocide occurred against the Maya population. The indigenous people know better than anyone the importance of democracy and the implications if Guatemala were to revert to an autocratic regime. The way they organize protests is creative, positive, and always peaceful. Every time the police or the military try to provoke, they engage in dialogue, showing that police officers and soldiers are also part of the people, negotiating compromises to avoid escalating violence. It's admirable, considering these people have been living under a system of apartheid and repression for centuries.

The political repression and gross human rights violations in Syria are well-known to all of us. Forced disappearances still occur on a large scale in the country, leaving deep wounds on families and society. It is shocking that geopolitical dynamics allow Assad to remain in power unpunished. Nevertheless, victims and Syrian human rights organizations show great resilience. In the absence of a political solution, they internationally advocate for justice, truth-seeking, and supporting victims, including at the UN level. For example, at Impunity Watch, we collaborate with the Truth and Justice Charter, an initiative of Syrian victim organizations that have developed a shared agenda of their priorities in terms of justice and victim support. We are deeply impressed by their work, and it is a privilege to work with them."

Can you share a personal experience or encounter during your work with Impunity Watch that has had a profound influence on your perspective and dedication to human rights?

"I think if you do this work, you are shaped by every encounter with people who have experienced great injustice. It teaches you to be humble, to realize that the real experts are those who have experienced this injustice. They know the context and know from practice what obstacles exist for justice and what is possible or not. I lived in Guatemala for six years, and from that experience, I started Impunity Watch. At that time, I worked with genocide victims and lived in their communities. In daily life, I saw how deeply rooted racism leads to structural injustice and inequality and how a culture of impunity fuels violence and secures the privileges of the status quo. But I also saw the tremendous dignity of people in the communities where I lived and how they collectively, in solidarity with each other, fought for recognition and justice.

When the peace accords were signed, the international community was optimistic; on paper, agreements for a peaceful and just society were laid out. There was a belief that this was now just a matter of implementation. However, actual change addressing the root causes of injustice is never automatic. Power structures do not relinquish privileges easily and do everything to protect those interests. For the victims, it was deeply frustrating that the international community portrayed Guatemala as changed, on the right path, while they experienced the opposite in their daily lives. It's hard to explain how frustrating it was for them to see how their narrative was ignored and overwritten by the narrative of the international community. This frustration was a powerful driver for starting Impunity Watch.

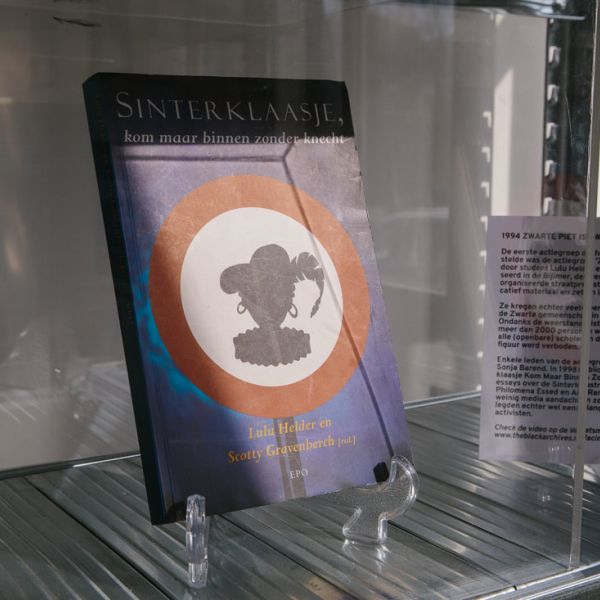

We began in Guatemala to do the first research on structural injustice and impunity. We aimed to expose and explain the structures that caused human rights violations and the political resistance against the structural changes required to prevent this. It's a strength of Impunity Watch that we always start by listening to the victims. In Guatemala, the victims were the best professors one could wish for to learn how deep the rabbit hole goes in terms of injustice. They taught us how crucial it is to understand the systemic aspects, which should not be overlooked. All of this taught me a great deal about humility and the importance of recognizing that the real experts are those who have lived through the injustices. It's our job to make sure that their expertise is recognized and that their experiences contribute to finding and promoting the most effective policies."

We see that this new approach of giving victims a seat at the table is opening the eyes of policymakers.

Is there a specific moment or achievement with Impunity Watch that stands out as a source of personal pride or fulfillment in promoting human rights?

"I always find that to be a somewhat risky question because it suggests that success is static and enduring, while the world is constantly evolving. What is a success today may be the opposite tomorrow. How do you measure success? Who determines what success is?

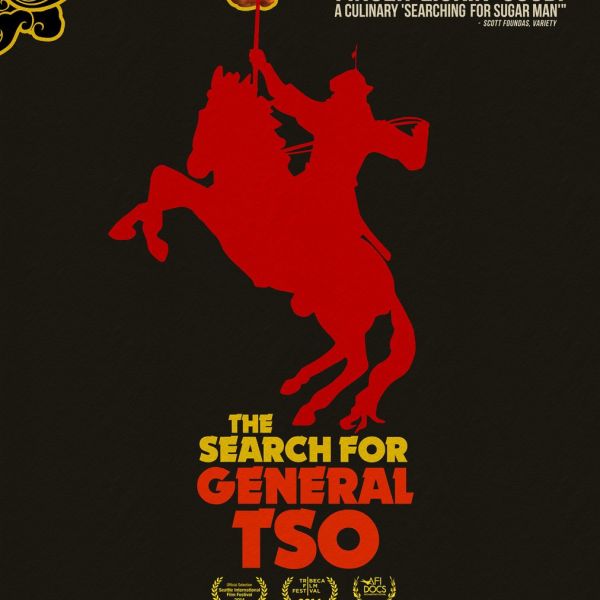

For us at Impunity Watch, it is important to engage in meaningful processes where we consider it a success when the voices of victims, survivors, and affected communities are heard, and they have a place at the table to shape policies that concern them. Our work with our Syrian partners, including the Truth and Justice Charter, is a good example of this; by bringing together victim groups with different experiences, they have been empowered to set a shared agenda of priorities. Based on that agenda, they began working. With the assistance of international partners such as Impunity Watch, they established a lobbying strategy to achieve those goals. With great success, for example, in the field of enforced disappearances. One goal of the groups was to establish an international UN mechanism for the search for the 'missing.' Although this goal initially seemed unattainable, the victims convinced the UN to establish an independent mechanism for 'missing persons in the Syrian Arab Republic,' which also aims to provide victims, families, and survivors with adequate assistance. Due to the central role that victim groups play in the establishment of this mechanism, they are also able to continuously monitor whether the mechanism remains in line with their needs.

We see that this new approach of giving victims a seat at the table is opening the eyes of policymakers. Previously, there was often a mindset of, 'Oh, it's so complicated, all these victims wanting things that are not realistic; we better keep them at a distance, or it will become too chaotic. We have international experts who can tell us what victims want and how we can shape policies best.' But if you have a different mindset, also at the international level, and you take the expertise and voice of victims seriously, you think about what might be a feasible response to their priorities, suddenly much more becomes possible. Victims and policymakers stand side by side, rather than far apart. You bridge the gap between grassroots knowledge and international policy. The starting point then becomes to think together about what we share, namely human rights and the desire to do something concrete and valuable for victims who have experienced so much suffering."

In your extensive career, is there a mentor or figure who has significantly influenced your approach to human rights work?

"I wouldn't be who I am without the experiences I've had in the field. I also wouldn't be who I am without my team. I have a fantastic team and learn every day from my colleagues, our partners, and the people we work with in the field. When I look at where we started and where we are now, we've grown very organically. The choices we've made are a result of what we've learned in the execution of our work, by listening to partners and colleagues and constantly making adjustments based on their feedback. My vision is that development can only happen if you dare to learn continuously. It's about the courage to experiment and therefore make mistakes. This way, we slowly develop an approach that works, and it's slightly different in every context. What we do in Burundi is very different from what we do in Guatemala. Impact also requires a constant proactive and critical dialogue with our partners. It's not that we blindly implement what our grassroots partners want. It's about learning together, reflecting together on whether the approach is working, and being able to question each other honestly. In doing so, we trust that our partners have the knowledge of the context and can assess what is possible and not possible at that moment without losing sight of larger goals."

How do you personally stay hopeful and motivated in situations where progress seems slow or challenges appear insurmountable?

"I'm going to say something very old-fashioned that may not be very fashionable nowadays, and that is: solidarity. When you work with people and you feel the solidarity because you believe in something together and work towards it together, that, for me, is the most powerful driving force. Despite concerns about the political developments and course in our country, we are still privileged here in the Netherlands. However, seeing and feeling that our partners in contexts like Syria, Iraq, DRC, Burundi, and Guatemala continue to have the energy to shoulder the responsibility, maintain a sense of humor, and have the drive to persevere, that affects you. It's a mistake to label people who have experienced severe human rights violations solely as victims. By doing so, you deprive them of their strength, their protagonism. It's impressive to see how much resilience, creativity, and clarity many of them possess in shaping their future, that of their loved ones, communities, and societies. In the countries where we work, the reality is harsh. Injustice is systematic. People have learned that despite setbacks, it is important to keep going. It's impressive to see people rise again and again, find new ways to make life meaningful, and continue to fight for an ideal of fairer societies, a fair world. That is impressive, something from which we can learn a lot in our privileged contexts.

I must say that leading a human rights organization in the current time is challenging. As I mentioned earlier, the world has changed. There are significant new political challenges, such as in the field of climate, with a global impact. The universality of human rights is no longer taken for granted. For some groups, it seems that we prioritize upholding human rights more than for others. Social media has brought many benefits; we now know much more about where injustice occurs in the world and what it looks like. We can mobilize more quickly. At the same time, social media contributes to polarization, opinions are based on perceptions rather than on serious analysis based on facts. This reinforces divisive thinking. Geopolitical relations in the world have changed. This black-and-white thinking does not bode well for policies needed to address the major new global problems. The importance of serious research as a basis for policy cannot be emphasized enough. At the same time, it is our duty as a human rights organization - especially in the face of all these challenges - to remain somewhat utopian, to believe that change is possible, and to make an extra effort to highlight good positive examples that also exist. We must continue to believe that alternatives are possible.

Another challenge we face in our field is the way we are funded. Many donors see organizations in our field as mere 'implementers' of their policies, which can undermine independence. To obtain funding, it is often necessary to focus on contexts and themes that are a priority for the donor but may not necessarily align with the strategic direction of organizations. Additionally, funding is often short-term, focused on short projects, followed by reporting on the successes of the project. However, what we have learned is that the struggle against impunity, building a truly more just society, is a long-term endeavor. It requires long-term processes and long-term solidarity with partners to work towards change, often in contexts that are not 'sexy' for donors at that moment. Lack of funding and political attention is a real challenge to continue the work. For us as a human rights organization, it means constantly weighing interests, making good choices, and being creative to remain true to our mission and our commitment to the contexts in which we want to be active."

I believe it is of great importance to continue doing so and engage in an open, respectful dialogue with people who think differently, even though it's not easy.

Outside the professional domain, how do you apply human rights principles in your daily life, and are there specific practices or habits that you consider important for promoting a culture of respect and dignity for everyone?

"I was at a party recently where some people who had voted for the PVV (Party for Freedom) were present. In the conversation, things were said like the Netherlands being the country with the most asylum seekers, and they are the reason for all our problems. Before I knew it, everyone was echoing each other, and perceptions and opinions were being presented as truths. Emotions ran high. In such a moment, the easiest way is to keep quiet and avoid the discussion. Trying to have a serious, honest discussion where you attempt to separate opinions from facts is not popular. Nevertheless, I believe it is of great importance to continue doing so and engage in an open, respectful dialogue with people who think differently, even though it's not easy. I believe that the best solutions are found through inclusive and respectful dialogue, even with people with whom we do not immediately agree. We have extensively discussed the dangers of polarization, of thinking in camps. The question is, what does it solve to remain opposed to each other? In this world, we have to work together. Particularly as human rights organizations, we have a great responsibility to advocate for the importance of the universality of human rights everywhere - both in our work and in our personal circles. As mentioned at the beginning: the world is a better place when we stand firm for that crucial principle."

Buiten het professionele domein, hoe ga je om met mensenrechtenprincipes in je dagelijks leven, en zijn er specifieke praktijken of gewoonten die je belangrijk vindt voor het bevorderen van een cultuur van respect en waardigheid voor iedereen?

“Ik was laatst op een feestje en daar waren wat mensen aanwezig die op de PVV hadden gestemd. In het gesprek werden er dingen gezegd als Nederland is het land met de meeste asielzoekers, zij zijn de reden voor al onze problemen. Voor ik het wist praatte iedereen elkaar na, en werden percepties en meningen als waarheden gepresenteerd. De emoties liepen flink op. Op zo’n moment is de makkelijkste weg om je mond te houden en de discussie uit de weg te gaan. Je maakt je niet populair om te proberen een serieuze eerlijke discussie te voeren waarbij je meningen van feiten probeert te scheiden. Toch denk ik dat het van groot belang is dat wel te blijven doen, en een open respectvolle dialoog aan te gaan met mensen die anders denken ook al is het niet makkelijk. Ik geloof dat de beste oplossingen worden gevonden door het voeren van een inclusieve en respectvolle dialoog, ook met mensen met wie we het niet direct eens zijn. Het gevaar van polarisering, van het denken in kampen hebben we uitgebreid besproken. De vraag is wat het oplost om tegenover elkaar te blijven staan. In deze wereld moeten we het met elkaar doen. Juist als mensenrechtenorganisaties hebben we een grote verantwoordelijkheid om overal - zowel in ons werk als in onze eigen persoonlijke cirkels – het belang van de universaliteit van mensenrechten uit te dragen. Zoals gezegd in het begin: de wereld is een betere plek als we pal staan voor dat cruciale principe.