The first ‘tree huggers’ were brave women

‘How have women influenced the rights for nature movement?’ On a cold and rainy Friday afternoon, environmental lawyer Jessica den Outer explored this question during a gathering for Women Connect, an Initiatives of Change Netherlands (IofC) initiative for and by women. At IofC, we’ve been following Jessica’s important work for years and at this particular gathering, we asked her to share (her) stories from a woman’s perspective.

Jessica is no stranger to IofC. In 2021, she was invited to do an online dialogue and interview as part of IofC’s Faith in Human Rights project. At 27 years old, Jessica has already built an impressive resume, having six awards to her name, including recognition as a Rights for Nature expert within the UN’s Harmony with Nature network. She has devoted her career to, in her own words, ‘an important mission: a green future for future generations.’

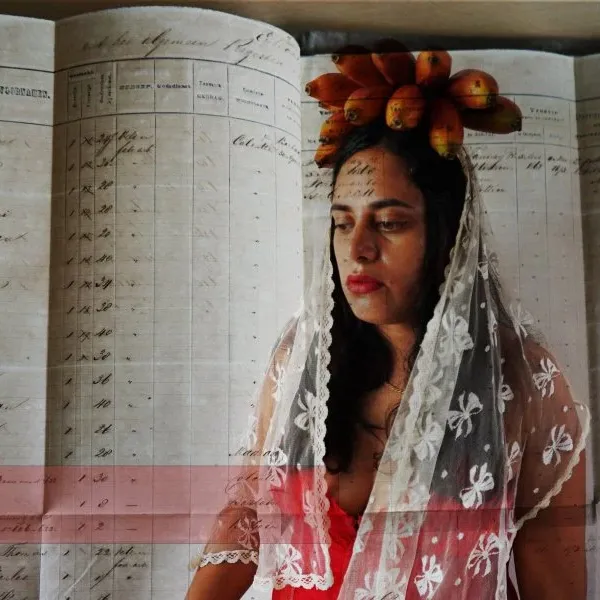

During the gathering, Jessica shared an impressive, but obscure story about the struggles of the women of the Chipko movement, the forerunner of what we nowadays call 'ecofeminism'. This movement started in 1973 when Indian women rebelled against commercial logging, or deforestation, with government permission. The women held vigil all night to guard their trees against the tree cutters until a few of the cutters gave up and left the village (see photo on the right). Because of their domestic responsibilities, these women were most affected by the disastrous effects of deforestation. In 1987, the Chipko movement received the Right Livelihood Award ‘for its dedication to the conservation, restoration and ecological voice of India's natural resources.’

Luckily, these extraordinary women aren’t fighting their battles alone: men have also played (and continue to play) an important role in the rights for nature movement. Jessica draws inspiration from the work of Christopher Stone (October 2, 1937 – May 14, 2021). Stone studied law at Yale Law School and taught at the University of Southern California for over fifty years. In his essay entitled Should Trees Have Standing?: Towards Legal Rights for Natural Objects (1972), he advocated for granting legal rights to forests and oceans.

Inspired by Stone's ideas, Jessica initiated a petition in 2022, addressed to the House of Representatives to investigate whether the river Maas can be granted legal personhood. She voiced her concerns as follows: 'The level of pollution that we see today violates the right of the river to flow freely and to be free of pollution. Legislation must change so that the Maas can be treated as a legal entity as the first river in the Netherlands and Europe.’ 3

While Christopher Stone's ideas were initially met with derision, numerous prominent environmental activists have now expressed their support. This delay is not surprising when you consider that not too long ago, women, children, and people of color had few to no rights. Fortunately, the rights for nature movement is becoming more visible and influential.

In the Anthropocene, the geological era of the human, we tend to imagine ourselves as rulers of nature. We believe that we have the right to influence and consume everything around us. These human activities lead to disastrous consequences for our planet: and climate change is one of them. We find a radically different worldview among various indigenous people, who consider humans as part of nature, and who show respect for all living things. Thanks to this philosophy, these people have been able to live in harmony with nature for centuries.

Jessica lists instances from countries in which nature is already given rights, thanks to the voice of indigenous people. In 2008, Ecuador incorporated the Rights of Nature into its constitution for the first time. In 2017, the river Whanganui in New Zealand was granted legal rights as the first river in the world, thanks to the Maori people. In 2022, Spain was the first European country to grant rights to the El Mar Menor lagoon to combat pollution. Bangladesh has granted rights to rivers and streams. In Brazil, the river San Francisco and the river Doce were recognized as legal entities, as was the Atrató River in Colombia. Mexico City and the state of Oaxaca also put into the concept of rights for nature.

Jessica acknowledges that there have also been setbacks, particularly close to home, as her call for granting the Waddenzee has not been heard. Nonetheless, she continues to advocate tirelessly for her cause. During the Q&A session, she stressed that you don’t have to be lawyers to stand up for the rights for nature.

After this inspiring lecture, the participants discuss over drinks how the word ‘activist’ still evokes many negative associations, which prevents women from actively fighting for their ideals. How do activists deal with the pressures and prejudices that come with being an activist, a participant asked. How do you build resilience? And how do you manage your time?

Excellent questions to explore for another Initiatives of Change gathering!

This story was written by Uyen Lu and was originally posted on Februari, 14 on IofC