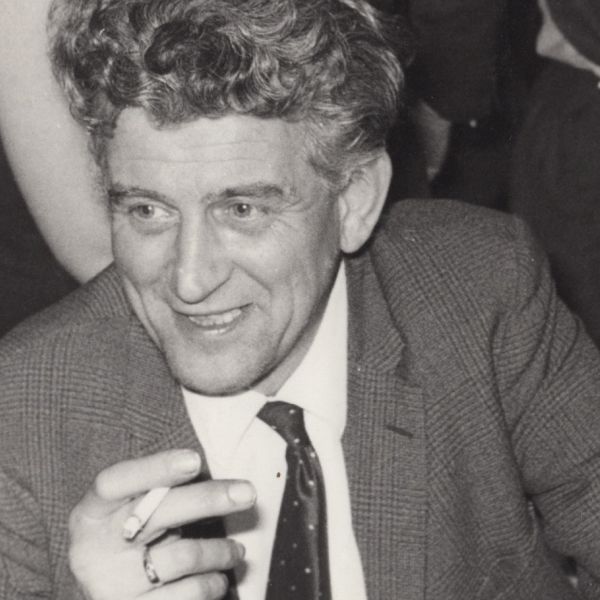

75 years of UN in 75 stories: Alexis Demirdijan

Alexis Demirdijan (1976) works in The Hague as an attorney for the International Criminal Court (ICC). Before that, he worked for the International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia. Although all witness hearings are prepared down to the details, there are always stories that unexpectedly affect him.

“All stories have to be told, so crimes can never be denied.”

For over 50 years, the UN fought to establish an international criminal court, but that goal was always made problematic by dissension among the UN member states. In recent decades, incidental tribunals set up to address specific war crimes

have dramatically accelerated the process of creating a permanent court. In 1998, a UN special committee finalised the draft text for the statutes of the International Criminal Court: the Rome Statute. In 2002, after the required number of 60 ratifications was reached, the International Criminal Court could begin. The ICC is a permanent court established to bring to justice those who have committed the most extreme forms of crime: genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, and who would otherwise enjoy impunity because their own countries cannot or do not wish to hold them accountable. Since its establishment, the court has heard 28 cases.

In 2020, a diplomatic conflict arose when the prosecutor for the ICC announced a new investigation into war crimes in Afghanistan. This would put not only the Taliban under scrutiny, but also American troops. The United States is not a party to the Rome Statute, and has threatened sanctions.

“Who are you convicting? The murderer of then, or the father of now?”

“I assisted a defendant in preparing his testimony for the tribunal. As an eighteen-year-old, he had been a willing participant in mass murder in the former Yugoslavia. When he had to appear in court for it, he was in his mid-30s and married. He spoke softly and exuded calm. At the end of the second day of his trial, he asked me whether I could do him a favour and buy a present for his son. Before my eyes I saw this man, the mindless murderer from the stories I had heard, turn into a caring father. In wars, people can do the most horrible things, but they can change how they feel. Who are you convicting? The murderer of then, or the father of now?”

Demirdijan was born in Lebanon to an Armenian family driven from Turkey after the genocide of the early 20th century. They then had to flee violence again when war broke out in Lebanon, travelling via France and Morocco to end up in Canada, where he grew up and completed his studies. Demirdijan does not believe that his background plays a role in his work for the ICC. “In the court, I am always impartial and independent.”

“Thanks to these personal stories, I am always reminded that my work is, first and foremost, about people”

Despite his professional demeanour, however, he is sometimes affected at unexpected moments. That happened, for example, when listening to the story of a survivor of a mass murder in Vukovar. “He told the story in court very matter-of-factly about how he jumped out of the truck, hid in a ditch, and that’s how he survived. He said it all without drama, without making accusations, without complaint at all. Everyone was impressed by this man. If he had been bitter, or angry, we would have understood, but he had risen above that.”

Because of stories like these, Demirdijan is always reminded that his work is, first and foremost, about people. “My primary motivation in doing this work is to make sure that all the stories can be heard. Only if we can make that happen can we make sure that crimes are not denied and perpetrators are called to account.”

There is only one place on earth where nearly all the nations of the world sit around the table: the United Nations. The UN focuses on issues that transcend the borders of countries or even affect the entire world, such as peace and security, climate change, education, health, cultural heritage, economic development, and more. To many, the work of the UN seems very abstract, but by engaging with rescue workers, peacekeepers, aid workers, diplomats, eyewitnesses, soldiers, and others involved with the UN, it becomes clear how important the work of this organization is. This is exactly what Humanity House has done. Unfortunately, this organization had to close its doors, but Just Peace and Museon-Omniversum have teamed up to preserve their stories. You can now find these stories on Just Peace's website, and some of them are also included in an exhibition about the UN at Museon-Omniversum.

The 75 Years of UN Stories were collected and curated by Frederiek Biemans for Humanity House.