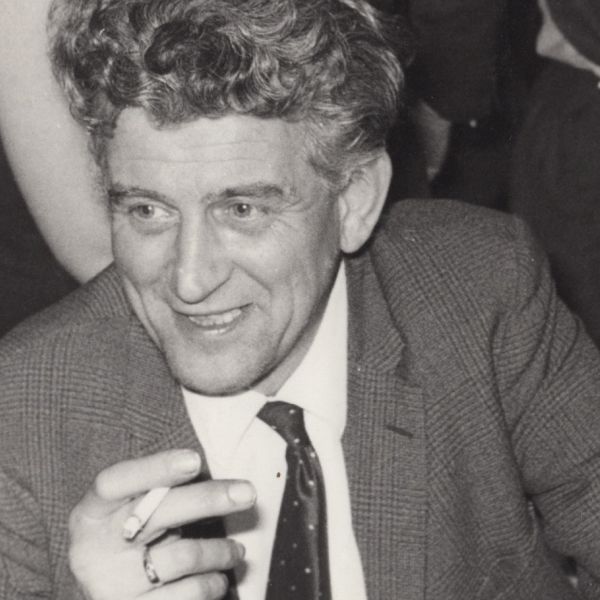

75 years of UN in 75 stories: Uğur Ümit Üngör

Professor Uğur Ümit Üngör (1980) is a sociologist, historian, professor of Holocaust and Genocide Studies at the University of Amsterdam, and senior researcher at the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies.

The General Assembly of the United Nations adopted the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide on 9 December 1948.

Article II of this convention states:

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

a. kiilling members of the group;

b. causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

c. deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

d. imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

e. forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

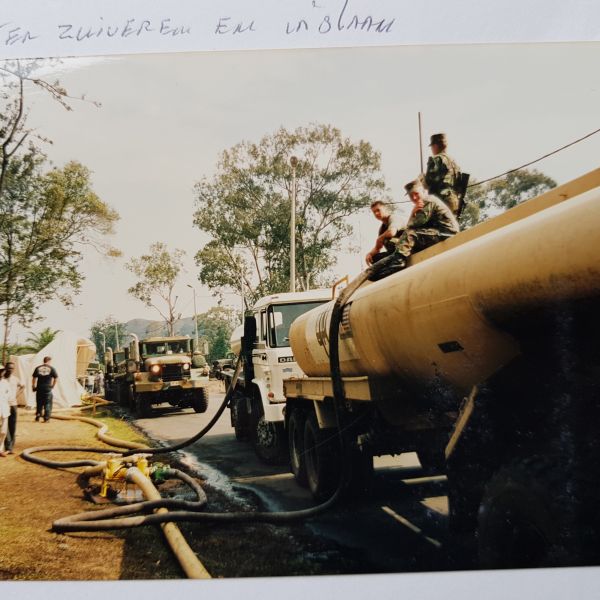

With this convention, the UN undertook a commitment for the prevention of genocide, but in practice the UN faces many obstacles in achieving this goal. Genocide has occurred since 1948: Cambodia in the 1970s, Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1995, Darfur after 2005. Even with troops on the ground, the UN was unable to prevent the murder of nearly one million Tutsis and moderate Hutus in 1994. At the end of 1994, the UN established the Rwanda Tribunal (ICTR) to bring those principally responsible to justice. The International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia, established in 1993, also tried a number of war criminals from the former Yugoslavia.

“Armeniërs en Turken komen uit hetzelfde gebied, delen dezelfde cultuur”

“During my studies, I read that the Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer compared the Holocaust to other genocides, and one that he referred to was the Armenian genocide. I was perplexed. How could it be that I didn’t know anything about this? My family originally came from Eastern Turkey, where the Armenians lived at that time. Had there been a genocide there? How come we never talked about it? I met Armenians for the first time in 2002 during a memorial ceremony. It felt comfortable. We come from the same area, we share the same culture.

That summer I travelled to Turkey. In the bookshops, I only found denial literature; on television I saw a historian disputing the facts. I asked my grandmother, ‘Were there ever Armenians living in our village?’ ‘Of course there were,’ she said, ‘but the government killed them.’ Other people I talked to confirmed it. How is it that a people can know something like this, and the government still denies it? How can a government murder its own citizens and get away with it? These are the types of questions that led me to specialise in Holocaust and genocide studies.

“How can a government murder its own citizens and get away with it?”

But when I really got inspired was one year later, at a conference about the prevention of genocide, when I met the Canadian UN General Romeo Dallaire. He had been a witness to a million Tutsis being slaughtered in 1994. He had saved a lot of people, but when he spoke it was about how frustrated he was about the ones he couldn’t save. I have the deepest respect for people like him, who help others under the most horrific circumstances and at great personal risk.

What I learned from Dallaire is that the system of the United Nations doesn’t work. Stateless lands are oppressed by the member nations of the UN. The mandate to intervene is in the hands of five powerful countries, each with a veto right and each with often conflicting interests. It would be better if the General Assembly made the decisions. That would increase the chances of responsible action.”

“He had saved a lot of people, but when he spoke it was about how frustrated he was about the ones he couldn’t save”

There is only one place on earth where nearly all the nations of the world sit around the table: the United Nations. The UN focuses on issues that transcend the borders of countries or even affect the entire world, such as peace and security, climate change, education, health, cultural heritage, economic development, and more. To many, the work of the UN seems very abstract, but by engaging with rescue workers, peacekeepers, aid workers, diplomats, eyewitnesses, soldiers, and others involved with the UN, it becomes clear how important the work of this organization is. This is exactly what Humanity House has done. Unfortunately, this organization had to close its doors, but Just Peace and Museon-Omniversum have teamed up to preserve their stories. You can now find these stories on Just Peace's website, and some of them are also included in an exhibition about the UN at Museon-Omniversum.

The 75 Years of UN Stories were collected and curated by Frederiek Biemans for Humanity House.